Sometimes A Startup Has To Seek Permission To Change The World

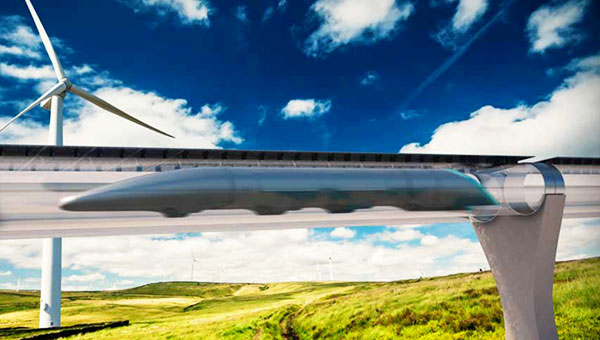

Imagine it’s noon and there’s a work emergency in the London office and you’re stuck in Manchester 260 miles away. It’s four-hour drive or a two-hour trip on National Rail. But that’s okay. You take out your mobile, order a self-driving vehicle to pick you up and take you to the Manchester Hyperloop portal. Thirty minutes later, you emerge from the London portal.

We’re a startup in Los Angeles commercializing the technology that can make that happen. Hyperloop is an all-electric, direct high-speed connection that shrinks the cost of time and distance. SpaceX founder Elon Musk floated the idea in 2013 to use linear electric motors to propel levitated vehicles at airplane speeds through near-vacuum tubes. Hamburg to Berlin in 19 minutes. Dubai to Abu Dhabi in 12 minutes. You can live in one city and commute to another in the time it takes to read this. The Hyperloop is autonomous, energy efficient, and we hope to to make it as comfortable as a Lexus and safer than a train — and much safer than a car.

This isn’t the stuff of science fiction. We demonstrated our propulsion system in May. We’re working toward a full-system test early next year at our site in the Nevada desert. We have commercial deals in Dubai, Russia, the Nordics, and the United States to produce detailed feasibility studies for passenger and cargo systems.

Elon Musk has joked that experts call the Hyperloop either obvious — or impossible. We believe it is possible, but we face some difficult challenges unlike those faced by most tech startups.

Most fledgling firms raise a few million, build some software, launch, listen and iterate. Our engineering challenges are more complex; we’re building something that has never existing before, such as a non-mechanical switching system for pods moving at subsonic speeds spaced only 10 seconds apart.

What we’re doing is more like SpaceX or Tesla, except that some engineers knew how to build rockets and cars. Our technology stack doesn’t even exist. We also need to innovate in areas of finance, in order to raise the eventual tens of billions of dollars to finance Hyperloop projects worldwide. Our regulatory challenges would also keep lawyers up at night; we need to work with regulators and state agencies to create a new legal framework under which Hyperloop can operate safely for all.

While the engineering and finance teams address some of the challenges, the regulatory challenges fall to the many of us across the business and legal teams. Here are three ways we’re going about addressing our peculiar regulatory challenges.

First, we will ask for permission and not seek forgiveness. Uber, Airbnb, Google, PayPal have all pushed the envelope of what’s legally permitted with more successes than defeats. They’re super smart companies. But we can’t operate that way. Like companies deploying phone networks or building bridges, we need permission even before we sell a service. We do not have the luxury of merely asking for forgiveness afterwards. We have to work with government agencies to make the system failsafe.

We are actually big fans of regulation, when it makes sense and is appropriate. The public should have assurances that a government agency has been involved to ensure appropriate access to rights of way and sufficient safety protocols. We are addressing this challenge partly by openly working with governments and partnering with entities that have considerable experience with governments. For example, two of our investors are the global ports operator DP World (partially owned by the Dubai government) and SNCF (France’s state-owned railway). Partnerships like these will provide tremendous insight into how governments entities work and how we can work with them.

Second, we will need a new framework of regulation. The Hyperloop doesn’t fit into any existing category. It has more in common with an airplane than a train, and not even much in common with a metro system. It is like a car in that you can leave when you want, but, technologically, has way more in common with aerospace. Most countries divide up oversight of transport among different modes — with a rail authority, an aviation authority, a transit authority, and so on. We need to create a compact with local government agencies to ensure that laws will be tailored to our technology and business, but that the public interest will also be served. We have to ensure we don’t fall between siloed regulators with conflicting statutes, thus setting back progress for largely arbitrary or historical reasons.

The youth, energy and grit of startup are formidable and necessary attributes to get a disruptive innovation to market quickly. The technology rightfully steals the headlines. But we need smart and open collaboration with government officials to ensure that our levitating pods take off.